[B]y the greatest miracle of all, this postwar world of super-international controls and coercions is also going to be a world of "free" international trade! Just what the government planners mean by free trade in this connection I am not sure, but we can be sure of some of the things they do not mean. They do not mean the freedom of ordinary people to buy and sell, lend and borrow, at whatever prices or rates they like and wherever they find it most profitable to do so. They do not mean the freedom of the plain citizen to raise as much of a given crop as he wishes, to come and go at will, to settle where he pleases, to take his capital and other belongings with him. They mean, I suspect the freedom of bureaucrats to settle these matters for him. And they tell him that if he docilely obeys the bureaucrats he will be rewarded by a rise in his living standards. But if the planners succeed in tying up the idea of international cooperation with the idea of increased State domination and control over economic life, the international controls of the future seem only too likely to follow the pattern of the past, in which case the plain man's living standards will decline with his liberties.

Monday, 8 December 2008

Henry Hazlitt on the so-called “free market”

Thursday, 5 July 2007

Restoring Liberties in 2007

Today, I intend to outline a number of proposals Smith makes in this sequel paper, Restoring Liberties.

It should be noted that Smith proposes these as points for discussion rather than suggesting that any or all should or would be adopted. This is understandable. Untrammelled democracy is a seductive system, as Mill himself noted when he argued that “The disposition of mankind, whether as rulers or as fellow citizens, to impose their own opinions and inclinations as a rule of conduct on others…is hardly ever kept under restraint by anything but want of power.” I have lost count of the number of people I have spoken to who are openly willing to force people to behave in a manner that will supposedly save them from themselves. A universal smoking ban and forced exercise camps are just around the corner.

Nonetheless, with organisations such as Direct Democracy agitating for a constitutional convention, and even the Government suggesting that we might actually begin to consider looking into going about wondering how to get together and discuss drafting a written constitution for the United Kingdom, now seems a good time to set out some thoughts for how to limit the power of the state and strengthen the protection of the individual.

He begins with the most obvious: a written constitution. The very first thing that must appear in a written constitution are rules on how the constitution itself can be amended. This is not small matter, as our current (un-codified) constitution can be changed at will by a simple majority of the two houses of parliament – indeed, probably by a resolute simple majority of just the lower house. Regional devolution and Lords reform may both have been welcome, but they nonetheless represent enormous constitutional change, and yet were required to meet only the same level of assent as a change in the motoring laws. The same is true of every European treaty that has been signed. One may fail to rest, far from assured that Gordon Brown’s newly proposed constitutional changes will be similarly enacted by a simple majority of perhaps just one house.

He begins with the most obvious: a written constitution. The very first thing that must appear in a written constitution are rules on how the constitution itself can be amended. This is not small matter, as our current (un-codified) constitution can be changed at will by a simple majority of the two houses of parliament – indeed, probably by a resolute simple majority of just the lower house. Regional devolution and Lords reform may both have been welcome, but they nonetheless represent enormous constitutional change, and yet were required to meet only the same level of assent as a change in the motoring laws. The same is true of every European treaty that has been signed. One may fail to rest, far from assured that Gordon Brown’s newly proposed constitutional changes will be similarly enacted by a simple majority of perhaps just one house.Smith proposes that in future the constitution should require both houses of parliament to pass the change by a two-thirds majority before the proposal is put to a referendum, where again a two thirds majority must support the change. Thus constitutional tinkering will be kept to a minimum, partisan advantage will be prevented, and yet the constitution will be able to develop if change is widely desired.

In addition, he proposes that each House should have a Constitutional Committee to warn parliamentarians to reject unconstitutional law. These should be empowered to refer existing legislation to a Constitutional Court. The establishment of a Constitutional Court would require a fundamental renegotiation of Britain’s membership of the EU, however, as citizens would otherwise be subject to unconstitutional European legislation that the Court could not – under present arrangements – strike down.

The second principle is that there must be absolute limits to the power of the state over individuals. This effectively means a Bill of Rights – though Smith overlooks the fact that this shifts the balance within society from a freedom-based society, where everything is permitted unless it is specifically banned, to a rights-based society where one has rights because one is given them by the constitution. I would therefore finesse Smith’s Bill of Rights by suggesting that it should be a fundamental statement of existing freedoms, should note in the preamble that the list is inviolable but is not exhaustive, and should include as its first clause the principle outlined above that freedom is the norm from which legislation and even the convention deviates.

The specific freedoms Smith identifies (and in brackets my own proposed alternatives, as he uses some terms that are unnecessarily limited) are freedom of speech (expression), movement, religion (conscience, or belief) and property. To these I would add freedom of association. Smith also includes ancient rights such as Habeas Corpus, trial by jury and rules on double jeopardy.

Smith also includes a general point: that government should not restrict activities of individuals that do not harm others or that harm them in a way that is understood and accepted (to permit surgery, boxing and sado-masochism) or is easily avoided (so that non-smokers are understood to be able to leave the room, rather than insisting others not smoke).

The third principle is that the constitution should prevent the tyranny of the majority. While this seems obvious, this is where it gets tricky. Smith supports a second chamber to oversee and review the lower house and the executive and delay their actions. However, he opposes election, fearing that it would merely be another democratic house that would represent a majoritarian view. He therefore proposes some combination from among expert peers (selected by an independent selection committee), indirectly elected peers (nominated by local councils so that they had an indirect mandate but protected regional interests) and citizen-jurors (chosen by lot to serve, as is the case with jury duty).

He also supports the monarchy on the grounds that state occasions cannot be used to flatter politicians, there is an ultimate veto to tyranny and the armed forces are not subject to the Prime Minister. I might add that there is something inherently humbling in the fact that the very first thing a Prime Minister must do is kneel before The State and kiss hands. Finally, he suggests that some far-reaching legislation that might particularly disadvantage minorities should require a larger level of majority (others have suggested two thirds).

He does not propose a directly elected executive; he feels there are enough checks and balances. To this I might add that the popular mandate that a directly elected Chief Executive would have would appear to entrench executive power and majoritarianism rather than limit it. Smith appears to have temporarily overlooked the lesson of his own paper, that democracy can be used to argue that the executive has a mandate from the people.

Fourthly, as well as limits to what Government can do, there should also be limits to how much, so as to restrict the amount of legislation that activist politicians can create. Parliamentary terms should be fixed in length and individual laws should have “sunset clauses”.

Fifthly, government should be accountable. There should be a federal structure with clear delineation of responsibilities; parliamentary oversight should be strengthened (including proper confirmation hearings) and budgets should be transparent, including the publication of costs associated with every policy.

Interestingly, in his comment to my original piece, Bishop Hill suggested that Smith may have missed a trick in limiting parliament with a Bill of Rights. It would be better to define what government may do and – in a reverse of the logic that should apply to humans – everything should be forbidden that is not explicitly permitted. Government, unlike people, should not be born free, nor should it ever be set free.

Smith’s own verdict on his work is bleak: “The vested interests of those who hold power generally disincline them towards any reforms that will reduce their ability to act as they wish.” When he calls for a constitutional convention to discuss a liberal future, he seems to ignore the crucial lesson of his work: that people’s urge to reproach, interfere and dictate is the source of our problems, and is likely to shape a constitutional convention. Before we begin considering a such a convention, we first need to ask what kind of society we want. Do we really want to be free, if it means others are free too? Or would we rather retain the right to coerce others to make them live in a manner that we see fit, even if we must ourselves bear coercion when we find ourselves in the minority?

When the Americans drafted their constitution, they may have been naïve enough to think that it would not be twisted and mutilated by overweening centralists and activist politicians, but at least they knew what they wanted from society. They wanted the traditional British liberties which free born British men had won over centuries. I am not sure that modern Britains want the same.

When the Americans drafted their constitution, they may have been naïve enough to think that it would not be twisted and mutilated by overweening centralists and activist politicians, but at least they knew what they wanted from society. They wanted the traditional British liberties which free born British men had won over centuries. I am not sure that modern Britains want the same.Wednesday, 4 July 2007

Taking Liberties since 1797

Entitled Taking Liberties (it seems that nothing is original), it was written by Craig F. Smith, who was at the time a research fellow at the University of Glasgow and has since become a lecturer in the Department of Moral Philosophy at the University of St Andrews. By chance I happen to also be reading a short summary of the works of Adam Smith to which he provided commentary.

The article begins by reminding us of one simple fact that we long seem to have forgotten. Democracy is not an end in itself, but a tool we created to promote freedom. The aim of democracy was to give to the people the power to sack their rulers (we may now prefer to see them as our delegated decision-makers, even our administrators). Such power would act as a very effective check on tyranny, for the tyrant could be easily overthrown without the need to shed blood.

What democracy was never intended to convey was sovereignty. Democracy was basically a negative power: the right to take power away from a leader. But it quickly began to mutate into a positive power, conveying a right to act in the name of the people. In the UK, a sense of “popular sovereignty” merged with the traditional sovereign powers of the monarch – exercised through his prime minister since the early C18th – to give parliament unlimited powers. Note, for example, that in the UK parliament may amend the constitution by a simple majority in both houses – unlike in the US, where a two thirds majority is needed in both houses and three quarters of the individual state legislatures. This raises the very value of the constitution; what is a constitution if it is not distinct from the general nature of law.

What democracy was never intended to convey was sovereignty. Democracy was basically a negative power: the right to take power away from a leader. But it quickly began to mutate into a positive power, conveying a right to act in the name of the people. In the UK, a sense of “popular sovereignty” merged with the traditional sovereign powers of the monarch – exercised through his prime minister since the early C18th – to give parliament unlimited powers. Note, for example, that in the UK parliament may amend the constitution by a simple majority in both houses – unlike in the US, where a two thirds majority is needed in both houses and three quarters of the individual state legislatures. This raises the very value of the constitution; what is a constitution if it is not distinct from the general nature of law.The idea that democracy conveys sovereignty is anathema to liberty. Let us ignore, for the moment, the flaws inherent in our form of democracy, whereby a government can be elected with a strong majority in parliament based on just 37 per cent of the votes cast and only 22 per cent of the whole electorate, which means a tiny minority of the whole population. Let us instead assume that all governments rule with the support of a majority of the people. Even so, they enable the majority to impose their will on the minority. This creates two inherent problems. As This merely ensures that a series of temporary coalitions can form around individual views, constantly marginalising new minorities. They may be marginalised because of their race (Jews, blacks), their religion (Muslims, atheists), their lifestyle (smokers, hunters) or their affluence (the very poor and the very rich). But because democracy enables governments to please all of the people some of the time, they need never please all of the people all of the time. All governments need is for most of the people to be happy most of the time.

Democracies also lead to the rise of the professional politician. These days it is axiomatic that politicians need to devote all their time to their jobs, and so should be paid a handsome salary. Without payment, only the rich would be able to afford to devote time to public office, which would lead to plutocracy. Yet paying permanent politicians has its own dangers which are often overlooked. One is that they can afford to devote time to re-election while their opponents have a proper job to do. Another is that they have the time and incentive to shape legislation to guarantee their re-election. The result is a bias towards activism; politicians want to be seen to do things, and preferably to “bring home the bacon”, to gain benefits for their constituents at the expense of the nation as a whole.

The result is that democracy actually undermines freedom. The two most obvious examples of this are the “ban culture” which prevails in Westminster, and the ever-spiralling tax rate.

Laws exist to ban things. Assuming that one accepts as a fundamental principle (and it is worth noting that this is true in Britain and America, but not in France) that everything is permitted that is not explicitly banned, then laws cannot convey freedoms (unless they repeal existing bans). Thus legislative activism naturally leads to greater limits to freedom. As Liberal Democrat Home Affairs spokesperson Nick Clegg MP has noted in a number of speeches, the Blair government introduced on average one new law every day. There are a lot of things we have been banned from doing over the past 10 years.

Laws exist to ban things. Assuming that one accepts as a fundamental principle (and it is worth noting that this is true in Britain and America, but not in France) that everything is permitted that is not explicitly banned, then laws cannot convey freedoms (unless they repeal existing bans). Thus legislative activism naturally leads to greater limits to freedom. As Liberal Democrat Home Affairs spokesperson Nick Clegg MP has noted in a number of speeches, the Blair government introduced on average one new law every day. There are a lot of things we have been banned from doing over the past 10 years.This is especially problematic due to a common confusion between the legislative and

administrative functions of the government. The recent smoking ban is an excellent example of this. The government has an administrative role (as master of the NHS) to promote public health and to keep costs under control. Unable to do this by administrative means, it uses legislation to ban the things that it cannot control (activities leading to lung-related illnesses). It cites health and safety legislation but ignores the freedom of individuals to enter and leave premises and to take or decline jobs. In effect, it uses its supposed sovereign power to forbid activity that is disapproves of for reasons of administrative convenience.

administrative functions of the government. The recent smoking ban is an excellent example of this. The government has an administrative role (as master of the NHS) to promote public health and to keep costs under control. Unable to do this by administrative means, it uses legislation to ban the things that it cannot control (activities leading to lung-related illnesses). It cites health and safety legislation but ignores the freedom of individuals to enter and leave premises and to take or decline jobs. In effect, it uses its supposed sovereign power to forbid activity that is disapproves of for reasons of administrative convenience.Other examples are more blatant; it is widely accepted that the ban on hunting with dogs was largely about playing to Labour’s gallery of class warriors and urban intellectuals.

The other inherent bias in the system is towards escalating taxation. Democracy enables the majority to impose their will on the minority. If the majority is poor and the minority rich, democracy acts as the great leveller (generally levelling down!), forcing the rich to give their money to the poor in direct transfers or by buying them services. As long as more people benefit than lose the measures will receive democratic support, even though the amount lost by the losers must equal the amount gained by the winners (in fact, the losers will lose more than the winners gain, as the inefficiencies of the system will lead to waste). Thus governments are inclined to continually raise taxation so as to dole out political favours to the masses at the expense of the productive few.

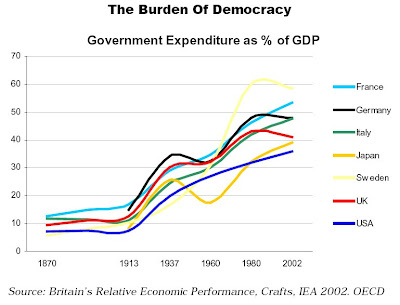

If this sounds doubtful, the following graph may be of note, demonstrating as it does the inexorable rise in Government expenditure in seven of the world’s leading democracies following the massive expansion of the franchise in the late C19th and early C20th.

The result is particularly hard to reverse because it generates a dependency culture, an addiction to the state as the solution to all our problems. “Liberty means responsibility,” observed George Bernard Shaw. “That is why most men dread it.” Throughout my lifetime every crisis – natural or man-made, financial, physical or moral – has been met with the demand that politicians take action. ‘Somebody should do something about this’ is a common cry among those who have lost the habit of asking ‘What can I do about this?’ So instead of buying our groceries in local shops we demand that regulators throttle the supermarkets; rather than choose a smoke-free pub we demand that smoking is banned in public places; rather than find a better job or undergo training we vote for tax-credits.

The result is particularly hard to reverse because it generates a dependency culture, an addiction to the state as the solution to all our problems. “Liberty means responsibility,” observed George Bernard Shaw. “That is why most men dread it.” Throughout my lifetime every crisis – natural or man-made, financial, physical or moral – has been met with the demand that politicians take action. ‘Somebody should do something about this’ is a common cry among those who have lost the habit of asking ‘What can I do about this?’ So instead of buying our groceries in local shops we demand that regulators throttle the supermarkets; rather than choose a smoke-free pub we demand that smoking is banned in public places; rather than find a better job or undergo training we vote for tax-credits. Democracy, as Churchill noted, “is the worst form of government except all the others”, and it is not my purpose nor is it Smith’s to argue that we should abandon democracy. But we need to remember that democracy exists to serve liberty – not vice versa. There is a reason why some of us consider ourselves Liberal Democrats. Of course there is a role for the state: classical liberalism is about limiting, not eliminating, it. We must uphold and even defend democracy, but we must be open minded about it, too, and ready to recognise its flaws. We have allowed democracy to run away with itself, and it has taken our freedom with it.

Democracy, as Churchill noted, “is the worst form of government except all the others”, and it is not my purpose nor is it Smith’s to argue that we should abandon democracy. But we need to remember that democracy exists to serve liberty – not vice versa. There is a reason why some of us consider ourselves Liberal Democrats. Of course there is a role for the state: classical liberalism is about limiting, not eliminating, it. We must uphold and even defend democracy, but we must be open minded about it, too, and ready to recognise its flaws. We have allowed democracy to run away with itself, and it has taken our freedom with it.

Craig F. Smith has some suggestions for how to restore liberty within democracy – though he  admits that they may be pie-in-the-sky and will certainly not be easily accepted. However, there a more fundamental lesson to learn. We have given up too much of our freedom by perpetuating the myth that in choosing who leads us we invest them with unlimited power. We must limit the power of parliament and the executive and re-focus responsibility in society on individuals. Bernard Shaw was right that freedom worries people and places great responsibilities upon them. But I hope Thomas Jefferson spoke for us all when he stated that he “would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty than to those attending too small a degree of it.”

admits that they may be pie-in-the-sky and will certainly not be easily accepted. However, there a more fundamental lesson to learn. We have given up too much of our freedom by perpetuating the myth that in choosing who leads us we invest them with unlimited power. We must limit the power of parliament and the executive and re-focus responsibility in society on individuals. Bernard Shaw was right that freedom worries people and places great responsibilities upon them. But I hope Thomas Jefferson spoke for us all when he stated that he “would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty than to those attending too small a degree of it.”

Sunday, 20 May 2007

Response from Simon Jenkins

I have had a response from Simon Jenkins to my letter about his comment piece in the Guardian last week suggesting that it is time that the Liberal Democrats disbanded.

I have had a response from Simon Jenkins to my letter about his comment piece in the Guardian last week suggesting that it is time that the Liberal Democrats disbanded.He actually sent it on 14 May 2007, but as my spam filter is not as discerning as the readers of the Guardian; it junked him, and I have only just come across the replay in my bulk mail.

His response is frankly shocking:

I have a suspicion that this is a standard reply, as it shows little evidence that he has read my letter. As I explained to him, the antithesis between left and right (Labour and Conservative wings , as he calls them) is archaic and does not represent the three competing philosophies that have shaped political discourse in Britain for two centuries: conservatism, liberalism and more lately socialism.Dear Tom Papworth

Thank you for your most interesting email. I have almost no quarrel with anything the Liberals have ever said. But if they disbanded and split into their more Labour and more Tory wings, think how clear-cut each general election might be.

With best wishes

Simon Jenkins

To say that he has almost no quarrel with anything that the Liberals have ever said, but nonetheless propose their disbandment, seems positively bizarre to me. It is usual in politics to support a party with which one almost always agrees.

As for how clear cut a general election could be, he has missed an obvious solution. Why not disband both the Liberal Democrats and the Labour Party, along with all the minor parties. Then general elections would be very clear cut indeed, with the Conservatives winning 646 seats and nobody else holding any. This is the sort of clear cut result one gets in places such as Cuba and North Korea, and leads to executive power that is in no way “diluted [and] unstable”, though one might wonder how it is to be held accountable.

Sir Simon clearly places the clarity of the outcome above the contestability

of the result. I disagree. The fact that individuals may choose to demur from the cosy consensus of two-party politics (those rare “Sincere friends of freedom” to whom I referred in my letter, in homage to Lord Acton) is healthy and valuable and should be encouraged.

of the result. I disagree. The fact that individuals may choose to demur from the cosy consensus of two-party politics (those rare “Sincere friends of freedom” to whom I referred in my letter, in homage to Lord Acton) is healthy and valuable and should be encouraged.That a plethora of political parties should compete with one another is essential if politics is not to result in the inevitable failure of that always accompanies duopoly. Duopolies always result in the provision of identical products by identical firms: on the rare occasions when different firms ran trains between the same cities, they ran them at the same times and charged the same ticket price, leading to no discernable difference for the customer and so no real competition. As Gordon Tullock explained in The Vote Motive, political parties in duopoly act in a similar way, gravitating towards the “centre” as they seek to capture the votes of the median voter. This results in stultifying consensus of the type we saw between Conservatives and Labour in the third quarter of the last century, and (as Sir Simon himself showed) between the Thatcherites and New Labour.

Yet while Sir Simon is clearly unhappy with the Thatcherite consensus, he actively decries the one major party that would seek to undermine that consensus and return power to local authorities (a big theme of at least two of his recent books). I can only believe that this is a result of cognitive dissonance: though the evidence is before his eyes, he cannot (or does not wish to) overcome the established thought-patterns that fused in his mind in an earlier era.

Thursday, 10 May 2007

A letter to Simon Jenkins

A cornucopia of Liberal Democrat bloggers have responded on their sites to Simon Jenkins’ comment piece in yesterday’s Guardian, in which launches a bitter but slightly confused attack on the Liberal Democrats.

A cornucopia of Liberal Democrat bloggers have responded on their sites to Simon Jenkins’ comment piece in yesterday’s Guardian, in which launches a bitter but slightly confused attack on the Liberal Democrats.I see no point in adding to James Graham’s fisking. Nor can I ever hope to match the wrath of Cicero. I have not the time to rival Mind Robber’s essay. I cannot hope for a wide a readership as Stephen Tall. I will defer to Duncan Borrowman's acidity.

The only way to add value to this debate is to take it to its source. I have therefore written an email to Sir Simon in which I point out that he has, himself, demonstrated what the Liberal Democrats are for in his most recent book.

I have also sent a truncated copy to the editor, in the hope of it being printed. Were it to be, I would have a wider readership than Stephen (for just one day). However, as I imagine Party grandees are even now formulating an official response, I suspect it is a vain hope. The full version would anyway never see the light of day, so I am reproducing it below. I hope you enjoy it.

Dear Simon,

I was surprised that you should question the role and purpose of the Liberal Democrats in your article in yesterday’s Guardian, as the answers were clearly contained within your most recent book.

Your article suggests that you continue to analyze politics through the lens of a right-left antithesis. Yet in Paradoxes of Power, on which you leant quite heavily for the first part of Thatcher and Sons, Alfred Sherman wrote that “We should long since have been liberated from shibboleths inherited from the parade of the Estates on the Versailles tennis court in 1789”. This is undoubtedly true.

As Friedrich Hayek suggested in explaining why he was not a conservative, there are in fact three distinct political traditions, each competing for space in the political arena. In answering your question, therefore, I would point out that the Liberal Democrats continue a long political tradition of liberalism, as opposed to both socialism and conservatism.

Of course the divisions between the political parties are not always as clear as ideology would suggest. There is a Social Democratic tendency within the Liberal Democrats, just as Roy Jenkins et. al. represented a liberal tendency within the socialist Labour Party. David Cameron claims to be a liberal Conservative, though in practice he seems to lean more towards a paternalistic High Tory dirigisme that shares ground with the socialists.

Ironically, Thatcher and Sons also indicates how this ideology translates to distinct policy, and further suggests that this policy is one with which you have sympathy. You note that the Thatcher government’s attempt to denationalise and deregulate the economy, to break up corporate interests and to inject market discipline into public services (the “First Revolution”) was pursued by means of a massive centralisation of authority in Whitehall, in the Treasury and within the office of the Prime Minister (the “Second Revolution”). While recognising the need for the first, you lament the second as both a failure and an encroachment on the liberty and diversity within British society. Yet as you clearly demonstrate, this centralism and arrogation of power has been the policy of both Conservative and Labour regimes for three decades.

The Liberal Democrats have consistently supported an alternative, local agenda that is in keeping with the liberal tradition that decision making should take place as near as possible to the citizen. While agreeing wholeheartedly with the First Revolution, the Liberal Democrats would seek to reverse the second, injecting greater power and autonomy into decrepit and demoralised local government. The Lib Dems would hand power to national, regional and local authorities that are more responsive to individual citizens, empowering individuals and communities and so encouraging greater political engagement.

The bulk of your article is in fact an expression of genuine concern that the outcome of a truly representative voting system may have on the unity and authority of the executive branch. This is a serious matter and deserves greater attention (though to continue with the status quo is not a satisfactory answer). However, to suggest that the difficulties presented by a system of proportional representation warrant the dismantling of one of Britain’s oldest and greatest political parties, with a distinct ideological tradition and substantial electoral success, is illogical.

Sincere friends of freedom may be rare, but no matter how the British polity is constituted, they will find a home within the Liberal Democratic Party.

Yours sincerely,

Thomas Papworth

Sunday, 22 April 2007

It must be the internet: we’ve mentioned the Nazis!

I have written before on the subject of banning holocaust denial. There is something truly grotesque about the attempt by some pseudo-historians and anti-Semites to rub the extermination of millions out of the pages of history. If any false-theory or misguided belief deserves to be banned it is this.

But it doesn’t. No matter how distasteful holocaust denial may seem, it is as nothing compared to the dangers of legislating against people's freedom of speech. It is trite beyond belief to equate one’s opponents with the Nazis, but when one begins to impinge upon the fundamental freedoms upon which a liberal society is built, one takes a first step down a slippery and dangerous path. Freedom must also include the freedom to be wrong, and liberty requires tolerance of those whose views challenge or even disgust us.

Why, anyway, are we so afraid of this tiny minority of twisted fools, that we should seek to muzzle them with the full force of the state? If we are so sure of our truths, can we not defend them with evidence and reason, rather than legislating to protect them? Let the holocaust deniers shout from the rooftops; they just draw attention to an evil that might otherwise fade into the distance.

As for European-wide legislation, it is neither necessary nor warranted. There is no compelling reason why EU member-states need to harmonise their laws on freedom of expression (though if they happened to all adopt a policy of tolerance towards opinions with which they did not disagree, I would rejoice!). The EU remains – at least for now – an single economic market, onto which has been grafted a few additional competences such as justice and foreign affairs co-operation. We remain 27 nation-states, each perfectly capable of deciding for itself what laws need apply in its jurisdiction.

The EU recognises this: it has a principle called “subsidiarity” that says that decisions should be taken at the level nearest the citizen (a principle that might usefully be applied within nation-states!). Sadly, the EU has always treated the subsidiarity clause with contempt. Like all bureaucracies, the Eurocracy seeks constantly to expand its powers. To our shame, Liberal Democrat euro-parliamentarians are all too ready to assist that creeping arrogation of power.

Thus this proposed law is the worst of both worlds, and highlights the fact that the EU is not in practice a liberal institution. The EU exists to further the free movement of goods, services, capital and labour and so foster greater harmony and co-operation between nations. In the process it has expanded its responsibilities far beyond what is necessary to achieve these goals, taking decision-making – and thus power – ever further away from the citizen.

As liberals we can be proud of our support for the Union, but that support must not blind us to its faults. We must not become partisans for the Union against our principles or the wishes of our countrymen. If we are going to fight to keep Britain in the Union, we must fight twice as hard to keep the Union liberal. If we fail in that, we will fail the British people twice over: we will saddle them with an illiberal institution; and when eventually it becomes to much to bear, we will share the blame for Britain’s withdrawal.

Monday, 26 March 2007

The Trap: Whatever happened to our dreams of freedom? (Conclusion)

Curtis was not shy in his conclusions. Isaiah Berlin was wrong, he said. The problem was not merely that the negative liberty that he had espoused had been mutated into its own form of positive liberty. Rather, it was Berlin’s very notion of negative liberty that was at fault. Positive liberty offers us a hopeful vision of a brighter and better future – it is a means to an end – whereas negative liberty offers no hope at all; it is nothing more than an end in itself. The world it conjured up was one without purpose. This narrow and limiting vision was a dangerous trap, offering nothing to counter the reactionary forces that would seek to sweep liberty aside by offering order and equality in place of freedom. A world of negative freedom was not inevitable, however, and Curtis ended with a paean for a rediscovery of a progressive politics, because positive freedom does not have to lead to tyranny.

It is ironic, then, that so much of this last programme demonstrated exactly the opposite. The positive liberty of the French and Algerian revolutionaries, of Sartre and his acolyte Pol Pot, of the Ayatollahs and all those other inspired revolutionaries – yes, even of Tony Blair’s attempt to

marry the two kinds of liberty – had always led to tyranny. In its mildest and most Fabian form, socialism in Britain led to Government officials dictating what individuals might earn and what businesses might charge, and as a result of its mildness it was more incompetent than brutal. Where positive liberty was carried to its logical conclusion, however, absolute poverty ensued – no matter how much relative poverty was alleviated – and dissenters went to the gallows or the gulags or just disappeared during the night.

marry the two kinds of liberty – had always led to tyranny. In its mildest and most Fabian form, socialism in Britain led to Government officials dictating what individuals might earn and what businesses might charge, and as a result of its mildness it was more incompetent than brutal. Where positive liberty was carried to its logical conclusion, however, absolute poverty ensued – no matter how much relative poverty was alleviated – and dissenters went to the gallows or the gulags or just disappeared during the night.Curtis refuses to see this because of his bias towards socialism, exposed by his claim that “the redistribution of land and wealth” were essential aspects of democracy. This is nonsense. Democracy may be a means to affect social change, but social change is not integral to democracy. It is integral to positive liberty, however, for it is the vision of a better world and the use of the levers of power – be they autocratic or democratic – to achieve that better world that is at the heart of positive liberty.

In fact, Curtis is wrong on a far more fundamental level. The ideal of negative liberty is neither narrow nor limiting, and certainly does not offer a bleak vision of the

future. On the contrary, it is offers the broadest and most enabling future imaginable, for what it recognises is that within each of us is the possibility of creating a better world, and that any one of us may chance upon a profound truth. Rather than be bound to follow the agreed path to progress – be it inspired by Marx or Mohammed or Mammon – we are each able to pursue a better world in our own way. If history is really the march of progress, its greatest lesson is that progress never came from societies agreeing in advance where the future lay and slavishly driving themselves to that goal. Progress came from a million tiny revolutions, from new ideas tried and new concepts espoused, from individuals free from the binding constraints of orthodoxy – or willing to risk pain and death to break those bonds. That progress is not achieved through shepherding society towards a cause, but through freeing men and women to act upon their own initiative.

future. On the contrary, it is offers the broadest and most enabling future imaginable, for what it recognises is that within each of us is the possibility of creating a better world, and that any one of us may chance upon a profound truth. Rather than be bound to follow the agreed path to progress – be it inspired by Marx or Mohammed or Mammon – we are each able to pursue a better world in our own way. If history is really the march of progress, its greatest lesson is that progress never came from societies agreeing in advance where the future lay and slavishly driving themselves to that goal. Progress came from a million tiny revolutions, from new ideas tried and new concepts espoused, from individuals free from the binding constraints of orthodoxy – or willing to risk pain and death to break those bonds. That progress is not achieved through shepherding society towards a cause, but through freeing men and women to act upon their own initiative.Isaiah Berlin called this "negative liberty" because freedom came from the absence of something – power and constraint. It suffers from nomenclature: the two types of liberty have semantic connotations. But in fact they are counterintuitive, for it is “negative liberty” that offers a more positive image of the future: one without coercion or conformism or crushing convention. It really does "Let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend". But even if Curtis were right, and the best that negative liberty could offer was freedom as an end in itself, is that so terrible? By being free, thinking individuals, seeking our own truth and looking to how we can improve the world in our own way, we become better people, more aware of ourselves and of those around us than we ever need do as followers of another’s path. If in the process we enjoy “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”, then so much the better. It may be negative liberty, but it is offers a more positive and more progressive image of the future than any other I have heard described.

Reviews of part 1, part 2 and part 3 are available separately.

The Trap: Whatever happened to our dreams of freedom? (Part 3)

Last night saw the third and final episode of Adam Curtis’s television series, The Trap: Whatever happened to our dreams of freedom?.

As I outlined in my reviews of the first and second episodes, this series has argued that the past thirty years has been dominated by a narrow and depressing view of freedom based on an assumption that cold rationality and a distrust of political leadership. Mr. Curtis has sought to undermine this concept. However, in doing so he has demonstrated his own failure to understand both the nature of freedom and the gulf between what has been delivered by political leaders and what individuals cry out for.

In this third post I will outline the programme for those who did not see it. I will address his conclusions in a final post, and there I will argue that he is wrong not only in his analysis but also in his fundamental call for a new type of freedom. In my writing, below, I will limit my comments (in the last and third from last paragraphs) to Curtis’s description of the experiences in Russia and in Iraq. Here Curtis was deliberately disingenuous, attempting to conjure a biased picture and so make it appear that the concept of liberty he opposes is to blame for the problems those countries experienced.

In the final episode, entitled We will force you to be free, Curtis abandoned his focus on psychology and Public Choice Theory, turning instead to the philosophical underpinnings of liberalism in the twentieth century. The leading exponent of liberty was the political philosopher Isaiah Berlin. In his essay Two Concepts of Liberty he presented two different images of freedom, which he called “Negative” and “Positive” liberty. Both were born of the French Revolution, but where the former sought freedom from constraint, the latter sought to make the world a better place. Put crudely, these have been described as “freedom to” and “freedom from”: the freedom to act as one sees fit (as long as it does not curtail the freedom of others, as Mill and others stressed), or the freedom from want that came from a progressive society.

Berlin believed that negative liberty was a great prize, freeing us from coercion by others and  tyranny by governments. Positive liberty, on the other hand, was a dangerous form of absolutism, for if there was only one ideal future, only one truth, then anything was justified to achieve that goal. “I object to paternalism,” Berlin explained, “to being told what to do.” His great fear was the tyranny of the Communist regimes that were at the time dominating Eastern Europe, but as his example he took the positive liberty preached by the Jacobins of the French Revolution: that the people were too stupid to appreciate freedom, so the state must “force them to be free”, using terror to force the changes necessary to make a better society. Negative liberty would protect us from this progressive tyranny. But Berlin also cautioned that the belief in negative liberty must never itself become an absolute destiny, for if it did it would morph into a form of positive liberty, with anything justified to achieve that end.

tyranny by governments. Positive liberty, on the other hand, was a dangerous form of absolutism, for if there was only one ideal future, only one truth, then anything was justified to achieve that goal. “I object to paternalism,” Berlin explained, “to being told what to do.” His great fear was the tyranny of the Communist regimes that were at the time dominating Eastern Europe, but as his example he took the positive liberty preached by the Jacobins of the French Revolution: that the people were too stupid to appreciate freedom, so the state must “force them to be free”, using terror to force the changes necessary to make a better society. Negative liberty would protect us from this progressive tyranny. But Berlin also cautioned that the belief in negative liberty must never itself become an absolute destiny, for if it did it would morph into a form of positive liberty, with anything justified to achieve that end.

Having set out the philosophical battlefield, Curtis began to populate it. Positive liberty was very popular in the middle of the twentieth century. Jean-Paul Sartre suggested that freedom was  shackled by society, and individuals had to break those shackles to be free. His views influenced Algerian revolutionaries who argued that the West controlled not by force of arms but of ideas, and that catharsis could be achieved by the cleansing fire of violence. Sartre also influenced Steve Biko, Che Guevara and Pol Pot. The views of these men fed back to Sartre, who advocated revolution to free society. This reached its apotheosis in the Khmer Rouge revolution in Cambodia, where revolutionaries sought to sweep aside the shackles that bound society by liquidating the entire middle class, even inviting the Cambodian Diaspora back to help rebuild society, only to butcher them on the runways as they stepped off the planes.

shackled by society, and individuals had to break those shackles to be free. His views influenced Algerian revolutionaries who argued that the West controlled not by force of arms but of ideas, and that catharsis could be achieved by the cleansing fire of violence. Sartre also influenced Steve Biko, Che Guevara and Pol Pot. The views of these men fed back to Sartre, who advocated revolution to free society. This reached its apotheosis in the Khmer Rouge revolution in Cambodia, where revolutionaries sought to sweep aside the shackles that bound society by liquidating the entire middle class, even inviting the Cambodian Diaspora back to help rebuild society, only to butcher them on the runways as they stepped off the planes.

The US reaction to the spread of revolutionary fervour was to promote reactionary forces; the “Realpolitik” of Henry Kissinger. But the support of dictators such as Pinochet and Marcos disgusted others in America – later known as the Neoconservatives – who felt that America should be promoting its values abroad rather than supping with the devil. When Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980, his Secretary of State told congress that there “are things worth fighting for”, and the administration introduced Project Democracy, a plan to promote democracy abroad using four key tools:

- Public support for democratic politics (including dropping the old, discredited allies)

- Promoting democracy abroad – but only in its electoral form, and not what Curtis referred to as the “other aspects of democracy: the redistribution of land and wealth”

- Undermining communist governments abroad (e.g. in Nicaragua)

- The creation of an Office of Public Diplomacy to spread propaganda to the American public.

The result were two scandals: one contemporary and one held over for the future. The contemporary scandal was the Iran-Contra Affair. The scandal for the future was the precedent that was set for spinning intelligence to justify wars for which there was no clear and present danger. The problem, noted Curtis (though he later seemed to conveniently forget it) was that the Neocons had reified Berlin’s fear: they were advocating forms of negative liberty in a positivist way: they would force us to be free.

Nobody noticed, however, because in 1989 Communism collapsed and history ended. Liberal  democracy had triumphed. Curtis chose to dwell on the results in Russia, where President Yeltsin followed Jeffrey Sachs advice and adopted a big bang approach to liberalising the economy, destroying elite institutions and freeing the people. To Curtis this was a disaster: prices shot up as soon as price controls were removed; people were issued with vouchers with which to buy stakes in privatising utilities, but they sold them for cash to the future Oligarchs who then snapped up the utilities for a windfall profit; objections in the Duma led Yeltsin to send in troops; finally there was a run on the banks and Russia defaulted on its debt. The results, argued Curtis, was that Russians turned their backs on the anarchy that had ensued and sought sanctuary in order. They willingly gave their freedoms away to President Putin, a reactionary autocrat who promised stability at the expense of liberty.

democracy had triumphed. Curtis chose to dwell on the results in Russia, where President Yeltsin followed Jeffrey Sachs advice and adopted a big bang approach to liberalising the economy, destroying elite institutions and freeing the people. To Curtis this was a disaster: prices shot up as soon as price controls were removed; people were issued with vouchers with which to buy stakes in privatising utilities, but they sold them for cash to the future Oligarchs who then snapped up the utilities for a windfall profit; objections in the Duma led Yeltsin to send in troops; finally there was a run on the banks and Russia defaulted on its debt. The results, argued Curtis, was that Russians turned their backs on the anarchy that had ensued and sought sanctuary in order. They willingly gave their freedoms away to President Putin, a reactionary autocrat who promised stability at the expense of liberty.

There is always a point in Curtis’s films where his bias is exposed. In this episode it was the Russian experience. His presentation of the Russian financial crisis crudely exploited time compression, disguising the five years that elapsed between the liberalisation and the financial difficulties. Nor did he mention the low price of commodities (on which Russia was dependent) in the late 1990s, or how much money would later flow into Russia as commodity prices rose. He ignored the knock-on effects from the Asian financial crisis, to which Russia was a sequel. And he said nothing of the Chechen War, surely a more effective tool in Putin’s armoury than the economy. Lastly, Curtis ignored the very different experience in much of Eastern Europe, where liberalisation has led to massive rises in living standards and where greater freedom has been welcomed. This analysis exposes Mr. Curtis as a partial and biased analyst. It does him no credit.

In the final part, Curtis suggested that Tony Blair was quite taken with the principles of negative liberty, but lamented the loss of idealism that positive liberty  conveyed. He wrote to Isaiah Berlin and asked whether it might be possible to synthesise the two, though the dying Berlin never replied. Blair went on to argue that it was the destiny of the West to spread liberty. Curtis argues that this was negative liberty as evangelism, but others might argue that it was not negative liberty at all. Blair was also aware that Public Choice Theory had undermined faith in politicians, so the only way to carry the people was – argued Curtis – to lie to them. Evidence for the Iraq war was spun, and Iraq was given a Russian-style dose of liberalising shock-therapy: everything was privatised and the Baath administrators were sacked.

conveyed. He wrote to Isaiah Berlin and asked whether it might be possible to synthesise the two, though the dying Berlin never replied. Blair went on to argue that it was the destiny of the West to spread liberty. Curtis argues that this was negative liberty as evangelism, but others might argue that it was not negative liberty at all. Blair was also aware that Public Choice Theory had undermined faith in politicians, so the only way to carry the people was – argued Curtis – to lie to them. Evidence for the Iraq war was spun, and Iraq was given a Russian-style dose of liberalising shock-therapy: everything was privatised and the Baath administrators were sacked.

The Iraq experience also encouraged distortion and bias from Curtis. He argued that the de-Baathification resulted from a liberal distrust of public officials. Not a word was said of the intellectual antecedent of this idea, the de-Nazification of Germany, or the fact that the vast majority of the Iraqi people were demanding the removal of their Baath tormentors. Even more unbelievably, Curtis claimed that it was the economic consequences of liberalisation and the lack of positive liberty at the heart of Iraqi democracy that triggered the insurgency, not a combination of Sunni ex-Baath rejectionists and Al Qaeda-inspired fanatics, as every other commentator and expert has agreed. It was fabrication on a grand scale.

He was right in one area, though. The emergence of Islamic terrorism in Western cities has been used – by both Blair and President Bush, among others – to justify massive extensions of state power in an attempt to pre-empt crime and terrorism. This has gone beyond terror, however, to seek pre-emptive powers to control possible criminal and even anti-social behaviour. The result is a return to the arbitrary power of the state and the end of the very civil liberties that the West is claiming to protect. It is a bitter irony.

I have separately reviewed part 2 and part 3. Curtis's conclusion and my analysis of it are discussed in a final post.

Monday, 19 March 2007

The Trap: Whatever happened to our dreams of freedom? (part 2)

Last night BBC 2 showed the second episode of Adam Curtis’s new series, The Trap: Whatever happened to our dreams of freedom?

As I explained when I reviewed part 1, the general premise of the programmes is that over the past thirty years, trends in psychology and economics that viewed the people as a rational, selfish individuals interested only in personal gain have come to dominate public policy. Policy-makers have lost faith in the concept of public service and have instead applied market forces to public services in an attempt to give power to citizens (as consumers) and free them from the shackles of bureaucracy. However, Curtis argues that this has in fact backfired, leading to worsening inequality and a collapse in public services and political efficacy.

Part 2, subtitled The Lonely Robot, expanded on these themes with particular focus on the 1990s, and in so doing highlighted both the mistakes of what we call the Thatcherite Revolution and Mr. Curtis’s own erroneous analysis. I will explain these errors below, but first I will provide a synopsis of the programme. Those familiar with it may wish to skip the next six paragraphs and move on to my comments.

The programme began by returning to Buchanan’s Public Choice Theory, which argues that politicians and civil servants actually pursue their own rational interests rather than the public good. Curtis juxtaposed John Major’s efforts to create an internal market in public services that would use the rational interests of public servants to achieve public ends, with Bill Clinton’s interventionist presidential campaign, in which he publicly berated President Bush for his laissez faire approach, saying that if Bush would not use the powers of the presidency to improve America, he should stand aside for somebody who would. Clinton was elected, but before he took office was visited by Alan Greenspan and Gene Sperling, who explained to him that if he tried to intervene in the economy he would just worsen the economic crisis of the early 1990s. They convinced him that the power of governments to effect positive economic outcomes was a chimera; only the market could provide the prosperity America craved. Clinton accepted this advice and presided over one of the greatest economic booms in American history.

However, Curtis criticised the underlying basis of this belief. He argued that the consumer  society did not in fact reflect the economics of Adam Smith. Rather, its assumption of the rational individual pursuing self-interest ignored the sympathy and moral sentiment which Smith argued were essential to man’s role in society. Instead, the selfishness of the species stemmed from scientific theory. Curtis dwelt upon and later critiqued anthropological studies of the Yanomamö people of Central Brazil, and also noted the view (promoted by Richard Dawkins, among others) that animals – including man – were merely vehicles and tools for the promotion of their selfish genes. Meanwhile, the revolution in psychological diagnosis described in last week’s programme had led to around half the population reporting themselves as suffering psychological disorder. New drugs such as Prozac appeared to offer a cure. The result was that millions of people took drugs to “normalise” their behaviour and emotions – a practice that some interviewees believed threatened to create a static, stagnant society.

society did not in fact reflect the economics of Adam Smith. Rather, its assumption of the rational individual pursuing self-interest ignored the sympathy and moral sentiment which Smith argued were essential to man’s role in society. Instead, the selfishness of the species stemmed from scientific theory. Curtis dwelt upon and later critiqued anthropological studies of the Yanomamö people of Central Brazil, and also noted the view (promoted by Richard Dawkins, among others) that animals – including man – were merely vehicles and tools for the promotion of their selfish genes. Meanwhile, the revolution in psychological diagnosis described in last week’s programme had led to around half the population reporting themselves as suffering psychological disorder. New drugs such as Prozac appeared to offer a cure. The result was that millions of people took drugs to “normalise” their behaviour and emotions – a practice that some interviewees believed threatened to create a static, stagnant society.

Back in the world of public policy, 1997 saw New Labour elected to govern Britain. Labour took the distrust of policy-making to a new level, as demonstrated by the granting of independent powers to the Bank of England. Labour’s means of “incentivising” public servants was to set centralised targets and reward or penalise them accordingly. Curtis cited some of the more ridiculous examples of targets set by the Labour government, including:

- A community vibrancy index

- The quantification of bird-song in the countryside

- A target to reduce world conflict by 6 per cent

- A target to reduce malnutrition in Africa by 48 per cent

The result was not driven and measurable success, but what a member of The Audit Commission called a systemic “gaming of the system”. The NHS would employ people who’s job it was to greet people on admission so that they met their targets of seeing patients within a certain time, though no treatment was given; wheels were removed from trolleys and corridors were renamed wards so that patients could be counted as being in a bed in a ward; the police reclassified crimes as “incidents” so that crime fell; schools taught easy subjects and concentrated on mediocre children so as to raise the number of children gaining GCSE grades A-C. The result was a decline is social mobility to the point where a child born in Hackney was twice as likely to die in its first year than one born in Bexley.

Curtis also critiqued the supposed boom in the US. The apparent rise in the financial markets  was based increasingly on dodgy accounting practices rather than reality. Meanwhile the economic progress was increasingly one-sided: one interviewer highlighted three interesting comparative statistics:

was based increasingly on dodgy accounting practices rather than reality. Meanwhile the economic progress was increasingly one-sided: one interviewer highlighted three interesting comparative statistics:

- The real term after-tax income of a family in the lowest quintile fell between the 1970 and the 2000s

- The real term after-tax income of a family in the middle quintile rose only slight between the 1970 and the 2000s

- The real term after-tax income of a family in the top 1 per cent rose by an enormous amount between the 1970 and the 2000s

Thus Americans were not only becoming less equal; the poorest were getting poorer.

The result of the revolution of the last thirty years, concluded Curtis, was that politicians were weakened by a mistaken belief that they could not affect change or improve welfare. Politicians were emasculated and corrupted and felt powerless. Meanwhile, the masses were not fulfilled by either consumerism or politics, but were instead doping themselves up on psychiatric medicines. At the same time, scientific evidence was emerging that undermined the selfish-gene and anthropological evidence of the 1970s, John Nash – the father of game theory – had begun to repudiate much of his work, and the free market was under attack by economists who argued for greater intervention and critiqued the rational individual thesis.

So ended the second episode. The third promises to discuss the War on Terror and – I suspect – “spin”.

Sadly, the second programme lived up to all my expectations. Curtis is an excellent documentary maker, but while he highlights genuine and important crises within society and provides a plausible historic context, he tends to misinterpret the causes and thus advocate policies that would exacerbate rather than alleviate those problems.

For a start, Curtis is prone to simple mistakes. For example, his critique of the American economic experience in the 1990s made a schoolboy error, confusing the state of the financial markets with that of the economy. In fact, the eventual collapse in share prices as the Dot Com and dodgy-accounting bubbles both burst had almost no effect on the US economy – the 2001 recession was the shortest and least painful in American history. Similarly, the statistics about relative welfare did not explain how far this was a result of taxes undermining the incomes of the poor (the statistics being post-tax incomes which suffer from heavy taxation), or of the effects of immigrant labourers who generally take low-paid work at the bottom of the economic pile, thus lowering averages without adversely affecting anybody, while they are happy to make a new life for themselves and their families. Similarly, in comparing infant morality rates in two London boroughs, Curtis failed to clarify whether the widening gap was due to a decline in Hackney or an improvement in Bexley.

Other errors, however, are more substantial, and demonstrate that he has fundamentally misunderstood both the classical liberal case and the causes of Thatcherism’s failures. The fundamental example in The Trap is Curtis’s belief that market mechanisms have been injected into public services and have as a result created perverse incentives for deliverers to “game the system” by aiming at achieving targets rather than positive outcomes for citizens; that governments have acted upon the belief that bureaucracies serve their own interests first. This is a profound error. In fact, the supposedly-liberalising agenda of the three (soon to be four) Thatcherite Prime Ministers has been completely undermined by the distrust that both the Conservatives and Labour have for freedom and the market.

Instead of creating a true market, with individuals holding the power as consumers and using  their power over the money to reward success and punish failure, the past thirty years has seen the greatest centralisation of power in Britain since the Stewarts attempted to introduce an absolute monarchy. Distrustful of what a true market might produce, successive governments have endeavoured to micromanage the public services from Whitehall. Thus, instead of eliminating the power of self-interested bureaucrats, they have made local authorities and public services answerable to central government, made delivery departments answerable to the Treasury, and made the Treasury answerable to a small coterie around the Prime Minister and the Chancellor. This has led not to liberty and a genuine market, but to an over-regulated, over-centralised, overly-bureaucratic system. This is not what either classical- or neo-liberal economists would have suggested.

their power over the money to reward success and punish failure, the past thirty years has seen the greatest centralisation of power in Britain since the Stewarts attempted to introduce an absolute monarchy. Distrustful of what a true market might produce, successive governments have endeavoured to micromanage the public services from Whitehall. Thus, instead of eliminating the power of self-interested bureaucrats, they have made local authorities and public services answerable to central government, made delivery departments answerable to the Treasury, and made the Treasury answerable to a small coterie around the Prime Minister and the Chancellor. This has led not to liberty and a genuine market, but to an over-regulated, over-centralised, overly-bureaucratic system. This is not what either classical- or neo-liberal economists would have suggested.

A real market that genuinely empowered people and lifted the dead hand of bureaucracy from our shoulders would put citizens in control. Rather than being answerable to civil servants in Whitehall, deliverers would be answerable to citizens through the latter’s ability to allocate funding. As Friedman demonstrated in theory and Sweden demonstrated in practice, voucher schemes not only drive up standards but they are particularly beneficial to the poorest in society. Sweden – that paragon on Social Democracy – has similarly had a very positive experience with creating a healthcare market.

Sadly, this kind of freedom is not to Curtis’s taste. For him the volatility and unpredictability of the market is disturbing, and the freedom of the individual is a myth. He prefers the certainties of Statism and the comfort of the community. But with the lack of hindsight that only a shift of generation can provide, he ignores the bleakness of the last period of interventionist government and the abject failure of Statist solutions. One need not look to pre-1990 Eastern Europe for evidence of the failure of state planning; dirigiste France’s youth unemployment of 25 per cent and Germany’s stagnant economy are lessons enough for us. Governments are incapable of managing so complex and delicate a system as the economy, which rely on incalculable pieces of information. Economies are, in essence, merely a mirror of society as a whole, and efforts to manage economies are therefore efforts to manage society. Whether it is through dictating how many hours an employee may work or through confiscating a portion of their earnings for central distribution, such efforts are inherently illiberal and should be kept to a bare minimum.

The desire of recent governments to end the old bureaucratic tyranny is laudable, but their  efforts have been risible and their methods misguided and ultimately counter-productive. Only by genuinely empowering citizens through giving them the power to allocate their resources – be they those they earn or those transferred to them by a welfare state – and allowing the consequences of those decisions to have their effect, will we improve the quality of public services and benefit society more generally. Into the bargain we will re-invigorate the population who, being now in control of their own destiny and no longer supplicants at the mercy of the state, will rediscover the moral sentiments that Smith and Mill thought vital elements of a fully rounded person.

efforts have been risible and their methods misguided and ultimately counter-productive. Only by genuinely empowering citizens through giving them the power to allocate their resources – be they those they earn or those transferred to them by a welfare state – and allowing the consequences of those decisions to have their effect, will we improve the quality of public services and benefit society more generally. Into the bargain we will re-invigorate the population who, being now in control of their own destiny and no longer supplicants at the mercy of the state, will rediscover the moral sentiments that Smith and Mill thought vital elements of a fully rounded person.

I have separately reviewed part1 and part 3. Curtis's conclusion and my analysis of it are discussed in a final post.

Monday, 12 March 2007

The Trap: Whatever happened to our dreams of freedom? (part 1)

In the first part, subtitled F*** you, buddy!, Curtis discussed how various different branches of scientific thought converged around the paranoia born of the Cold War. My main criticism of the first episode was that it failed to do more than set the scene. It may be that this will lead to fascinating insights in the next two programmes (he has already promised to show how it all led to the culture of “spin”) but the fact remains that the programme did not stand alone, and left too much of the analysis for later episodes.

It began with F. A. Hayek’s warning (available in full or in summary) that governmental efforts to manage the economy would lead not to the tempering of the excesses of capitalism but down a road that led ultimately to enslavement by the state. In fact this was barely touched upon before Curtis had moved on, but before he did so he presented a vary negative view of Hayek’s position, suggesting that his belief in a self-correcting system, in which individuals pursuing self-interest would promote a common good, relied upon the assumption that mankind was essentially selfish and callous.

I will dwell upon that for a moment both because I feel it misrepresented Hayek’s views on liberty, and because it calls into question Curtis’s assessment of other strands of thinking during the programme, about which I have less knowledge and so cannot exercise judgement.. Hayek was quoted as saying that there was no room for altruism in his theory. However, as those who have read Hayek should recognise, his theory does not in fact deny the altruism within people, nor does is suggest that altruism is not a good and worthy thing. Hayek’s concern was that government, with its unique power to coerce individuals, should not attempt to correct the self-regulating mechanism – even for altruistic ends – because ultimately those ends were the ends of fallible (and sometimes selfish) individuals. Instead it should create a sound and predictable legal framework that protected the liberty of individuals, who would then be free to pursue their own interests (even altruistic ones) that would as a by-product benefit mankind. This belief goes back at least as far as Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”.

The programme’s quickly moved on the main point, which was that there were those who thought that mankind could be liberated by rationalising him as an isolated, self-interested and ultimately callous creature (a rather sinister version of the individual at the heart of the Enlightenment). I will attempt to summarise this, though as I only have a limited knowledge of the subject matter I may make some errors – which may be due to my misunderstanding the programme or to its misrepresentation of the facts.

The story begins with the Game Theory logic of the Rand Corporation – promoted by the not-so-beautiful mind of John Nash – which suggested that individuals could never trust one another and so would always prosper if they adopted the most cynical assumptions about one another. Meanwhile, psychiatrist R. D. Laing had proved that much psychiatry was based not on science but a socially-constructed concept of the “normal”, and the role of psychiatry was to force those that were different back into the societal mould. Laing became the father of the anti-psychiatry movement and inspired the Rosenhan Experiment, which suggested that psychiatrists had no idea who was sane and who was not. The result was that psychiatrists were forced to admit that they had no idea what was wrong with the mind, and so the field shifted its attention from focussing on causes (schizophrenia, manic-depression) to symptoms defined by observable phenomena (ADHD, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder).

Meanwhile, back in economics, Public Choice Theory (outlined in, for example, The Vote Motive) had fatally undermined concepts such as the “public interest” and “public service”, demonstrating that politicians, civil servants and those working for the state were just as self-interested as those in any other walk of life. As Northcote Parkinson and Yes, Minister captured so humorously, everyone in public service was primarily trying to protect and promote their own interests; the “public interest” was just a cover for what was at best individuals’ concept of what was right and wrong, and at worst selfish rent-seeking.

The result of these three revolutions was a belief that the mess that many nations found themselves in by the 1960s and 1970s was caused by the naïve belief that the public good could be promoted by wise men in ivory towers rationalising the process with the disinterested altruism of platonic guardians. Not surprisingly, there were those who wanted to sweep aside this belief, and the entrenched interest groups that it protected. These included a number of right-wing think tanks. Their proposed solution was to exploit the self-interest of public servants to promote more effective outcomes: for example, by giving incentives to them to achieve results.

Sadly, this proved rather less successful in practice that in theory. Robert McNamara’s attempts to run the Vietnam War as a mathematical exercise, calculating exactly how much explosive tonnage needed to be dropped to achieve the cowed submission of the Communists, resulted in failure and resignation; in attempting to achieve body counts that met their targets, self-interested soldiers would kill anything that looked like a Viet Cong fighter, which in a guerrilla war meant just about anyone. Margaret Thatcher’s NHS reforms began the process – so beloved of Gordon Brown – of setting central targets for local hospitals and financially rewarding or penalising them accordingly. It has been an ill-starred venture.

And that is where the programme left off. There was no broad analysis or discussion; no sense of conclusion; and no clear vision of where the rest of the series would take us. We were left dangling in the wind, waiting for Mr. Curtis to explain it all on BBC2 next Sunday at 9pm and the Sunday following.

I have my reservations. Firstly, as I outlined regarding the approach to Hayek, Mr. Curtis’s analysis is not always correct – he is stronger on his psychiatric home-ground than on other topics. Secondly, I fear that his intention is to question much of what has happened in the past thirty years. While there have undoubtedly been colossal failures and terrible errors, there have also been successes and benefits: it is a sign of how much time has elapsed that some are now able to look fondly upon the 1960s and 1970s as though they were some sort of golden age, rather than a wasteland of inflation and unemployment, bubbling revolution and counter-revolution, and abject poverty. If it is Mr. Curtis’s intention to suggest that the positive elements of the revolution of the past thirty years – the deregulation and liberalisation that has led to wealth and freedom beyond the imagination of those living through the Winter of Discontent – have been accompanied by a creeping centralisation and rising state power, then he is correct (and in good journalistic company). But if, as I suspect, he intends to suggest that we would all be better off returning to the age of collectivism and public duty, of trusting citizens and paternalistic administrators, then he is simply swapping a flawed concept of freedom for no freedom at all.

I have separately reviewed part 2 and part 3. Curtis's conclusion and my analysis of it are discussed in a final post.

Wednesday, 7 March 2007

Mill, liberty and ID cards

On Monday night those of us not worn smooth by constant fringes over the weekend trudged our way to the National Liberal Club for an event organised by the John Stewart Mill Institute. The lecture was entitled John Stewart Mill and Actual Liberty, and was presented by the fantastically bemaned Professor A C Grayling, professor of philosophy at Birkbeck College, London.

On Monday night those of us not worn smooth by constant fringes over the weekend trudged our way to the National Liberal Club for an event organised by the John Stewart Mill Institute. The lecture was entitled John Stewart Mill and Actual Liberty, and was presented by the fantastically bemaned Professor A C Grayling, professor of philosophy at Birkbeck College, London.Grayling sought to set our understanding of liberty and that of Mill in the context of what he saw as the emerging concept of liberty through the ages. At the end he sought to link this to “actual liberty” in our time, concentrating mostly on the excrescence that is the Government’s ID card scheme.