I recently read the most fascinating article on how democracy undermines liberty.

Entitled

Taking Liberties (it seems that

nothing is

original), it was written by Craig F. Smith, who was at the time a research fellow at the University of Glasgow and has since become a lecturer in the Department of Moral Philosophy at the University of St Andrews. By chance I happen to also be reading a

short summary of the works of Adam Smith to which he provided commentary.

The article begins by reminding us of one simple fact that we long seem to have forgotten. Democracy is not an end in itself, but a tool we created to promote freedom. The aim of democracy was to give to the people the power to sack their rulers (we may now prefer to see them as our delegated decision-makers, even our administrators). Such power would act as a very effective check on tyranny, for the tyrant could be easily overthrown without the need to shed blood.

What democracy was never intended to convey was sovereignty. Democracy was basically a negative power: the right to take power away from a leader. But it quickly began to mutate into a positive power, conveying a right to act in the name of the people. In the UK, a sense of “popular sovereignty” merged with the traditional sovereign powers of the monarch – exercised through his prime minister since the

early C18th – to give parliament unlimited powers. Note, for example, that in the UK parliament may amend the constitution by a simple majority in both houses – unlike

in the US, where a two thirds majority is needed in both houses and three quarters of the individual state legislatures. This raises the very value of the constitution; what is a constitution if it is not distinct from the general nature of law.

The idea that democracy conveys sovereignty is anathema to liberty. Let us ignore, for the moment, the flaws inherent in our form of democracy, whereby a government can be elected with a strong majority in parliament based on just 37 per cent of the votes cast and only 22 per cent of the whole electorate, which means a tiny minority of the whole population. Let us instead assume that all governments rule with the support of a majority of the people. Even so, they enable the majority to impose their will on the minority. This creates two inherent problems. As This merely ensures that a series of temporary coalitions can form around individual views, constantly marginalising new minorities. They may be marginalised because of their race (Jews, blacks), their religion (Muslims, atheists), their lifestyle (smokers, hunters) or their affluence (the very poor and the very rich). But because democracy enables governments to please all of the people some of the time, they need never please all of the people all of the time. All governments need is for most of the people to be happy most of the time.

Democracies also lead to the rise of the professional politician. These days it is axiomatic that politicians need to devote all their time to their jobs, and so should be paid a handsome salary. Without payment, only the rich would be able to afford to devote time to public office, which would lead to plutocracy. Yet paying permanent politicians has its own dangers which are often overlooked. One is that they can afford to devote time to re-election while their opponents have a proper job to do. Another is that they have the time and incentive to shape legislation to guarantee their re-election. The result is a bias towards activism; politicians want to be seen to do things, and preferably to “bring home the bacon”, to gain benefits for their constituents at the expense of the nation as a whole.

The result is that democracy actually undermines freedom. The two most obvious examples of this are the “ban culture” which prevails in Westminster, and the ever-spiralling tax rate.

Laws exist to ban things. Assuming that one accepts as a fundamental principle (and it is worth noting that this is true in Britain and America, but not in France) that everything is permitted that is not explicitly banned, then laws cannot convey freedoms (unless they

repeal existing bans). Thus legislative activism naturally leads to greater limits to freedom. As Liberal Democrat Home Affairs spokesperson

Nick Clegg MP has noted in a number of speeches, the Blair government introduced on average one new law every day. There are a lot of things we have been banned from doing over the past 10 years.

This is especially problematic due to a common confusion between the legislative and

administrative functions of the government. The recent

smoking ban is an excellent example of this. The government has an administrative role (as master of the NHS) to promote public health and to keep costs under control. Unable to do this by administrative means, it uses legislation to ban the things that it cannot control (activities leading to lung-related illnesses). It cites health and safety legislation but ignores the freedom of individuals to enter and leave premises and to take or decline jobs. In effect, it uses its supposed sovereign power to forbid activity that is disapproves of for reasons of administrative convenience.

Other examples are more blatant; it is widely accepted that the ban on hunting with dogs was largely about playing to Labour’s gallery of class warriors and urban intellectuals.

The other inherent bias in the system is towards escalating taxation. Democracy enables the majority to impose their will on the minority. If the majority is poor and the minority rich, democracy acts as the great leveller (generally levelling down!), forcing the rich to give their money to the poor in direct transfers or by buying them services. As long as more people benefit than lose the measures will receive democratic support, even though the amount lost by the losers must equal the amount gained by the winners (in fact, the losers will lose more than the winners gain, as the inefficiencies of the system will lead to waste). Thus governments are inclined to continually raise taxation so as to dole out political favours to the masses at the expense of the productive few.

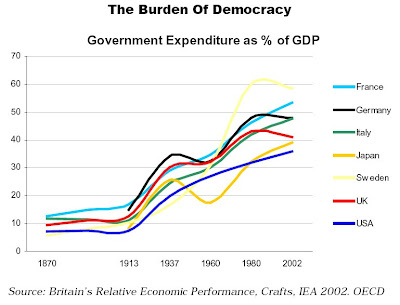

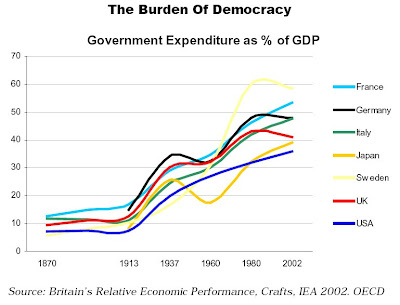

If this sounds doubtful, the following graph may be of note, demonstrating as it does the inexorable rise in Government expenditure in seven of the world’s leading democracies following the massive expansion of the franchise in the late C19th and early C20th.

The result is particularly hard to reverse because it generates a dependency culture, an addiction to the state as the solution to all our problems. “Liberty means responsibility,” observed George Bernard Shaw. “That is why most men dread it.” Throughout my lifetime every crisis – natural or man-made, financial, physical or moral – has been met with the demand that politicians take action. ‘Somebody should do something about this’ is a common cry among those who have lost the habit of asking ‘What can I do about this?’ So instead of buying our groceries in local shops we demand that regulators throttle the supermarkets; rather than choose a smoke-free pub we demand that smoking is banned in public places; rather than find a better job or undergo training we vote for tax-credits.

The result is particularly hard to reverse because it generates a dependency culture, an addiction to the state as the solution to all our problems. “Liberty means responsibility,” observed George Bernard Shaw. “That is why most men dread it.” Throughout my lifetime every crisis – natural or man-made, financial, physical or moral – has been met with the demand that politicians take action. ‘Somebody should do something about this’ is a common cry among those who have lost the habit of asking ‘What can I do about this?’ So instead of buying our groceries in local shops we demand that regulators throttle the supermarkets; rather than choose a smoke-free pub we demand that smoking is banned in public places; rather than find a better job or undergo training we vote for tax-credits.

Democracy, as Churchill noted, “is the worst form of government except all the others”, and it is not my purpose nor is it Smith’s to argue that we should abandon democracy. But we need to remember that democracy exists to serve liberty – not vice versa. There is a reason why some of us consider ourselves Liberal Democrats. Of course there is a role for the state: classical liberalism is about limiting, not eliminating, it. We must uphold and even defend democracy, but we must be open minded about it, too, and ready to recognise its flaws. We have allowed democracy to run away with itself, and it has taken our freedom with it.

Democracy, as Churchill noted, “is the worst form of government except all the others”, and it is not my purpose nor is it Smith’s to argue that we should abandon democracy. But we need to remember that democracy exists to serve liberty – not vice versa. There is a reason why some of us consider ourselves Liberal Democrats. Of course there is a role for the state: classical liberalism is about limiting, not eliminating, it. We must uphold and even defend democracy, but we must be open minded about it, too, and ready to recognise its flaws. We have allowed democracy to run away with itself, and it has taken our freedom with it.

Craig F. Smith has some suggestions for how to restore liberty within democracy – though he  admits that they may be pie-in-the-sky and will certainly not be easily accepted. However, there a more fundamental lesson to learn. We have given up too much of our freedom by perpetuating the myth that in choosing who leads us we invest them with unlimited power. We must limit the power of parliament and the executive and re-focus responsibility in society on individuals. Bernard Shaw was right that freedom worries people and places great responsibilities upon them. But I hope Thomas Jefferson spoke for us all when he stated that he “would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty than to those attending too small a degree of it.”

admits that they may be pie-in-the-sky and will certainly not be easily accepted. However, there a more fundamental lesson to learn. We have given up too much of our freedom by perpetuating the myth that in choosing who leads us we invest them with unlimited power. We must limit the power of parliament and the executive and re-focus responsibility in society on individuals. Bernard Shaw was right that freedom worries people and places great responsibilities upon them. But I hope Thomas Jefferson spoke for us all when he stated that he “would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty than to those attending too small a degree of it.”

NOTE: The title of this article borrows from the film Taking Liberties since 1997, but refers to the first imposition of Income Tax in Great Britain.

exempted disabled drivers from paying VAT on new cars. This immediately strikes me as odd, in that there is no inherent reason why a disabled person – even one with mobility difficulties – would have greater need for a car than any particular other person. For one thing, it smacks of lumping all disabled people together and assuming that their needs are identical, whereas in fact the need for motorised transport probably varies as widely among disabled people as it does among the general population. Secondly, there are plenty of non-disabled people who desperately need a car – perhaps to convey their children to school, to go to work or attend hospital. They do not get tax breaks to buy one, however. One might also question why the benefit is not being channelled into public transport, as the government claims to want to encourage us out of cars.

exempted disabled drivers from paying VAT on new cars. This immediately strikes me as odd, in that there is no inherent reason why a disabled person – even one with mobility difficulties – would have greater need for a car than any particular other person. For one thing, it smacks of lumping all disabled people together and assuming that their needs are identical, whereas in fact the need for motorised transport probably varies as widely among disabled people as it does among the general population. Secondly, there are plenty of non-disabled people who desperately need a car – perhaps to convey their children to school, to go to work or attend hospital. They do not get tax breaks to buy one, however. One might also question why the benefit is not being channelled into public transport, as the government claims to want to encourage us out of cars. The paternalism is only half of the problem, however. The other half is that, unsurprisingly, enterprising people have learnt to game the system. Firstly, the VAT exemption does not appear to be capped. Thus it applies not only to a Nissan Micra, on which the VAT might be just over £1,000. It appears it also applies to “top-of-the-range Land Rovers, Bentleys, Maseratis and Lamborghinis, costing up to £70,000. That means that [disabled drivers] could save as much as £12,250 on each transaction in VAT.”

The paternalism is only half of the problem, however. The other half is that, unsurprisingly, enterprising people have learnt to game the system. Firstly, the VAT exemption does not appear to be capped. Thus it applies not only to a Nissan Micra, on which the VAT might be just over £1,000. It appears it also applies to “top-of-the-range Land Rovers, Bentleys, Maseratis and Lamborghinis, costing up to £70,000. That means that [disabled drivers] could save as much as £12,250 on each transaction in VAT.”

On 11 July he was

On 11 July he was